While the Roman Catholic Church is synonymous with the Eternal City (and Italian capital), the greatest monument from its medieval heyday actually stands in southern France. The relic of the Papacy’s brief departure from Rome, the Palais des Papes (“Palace of the Popes”) in Avignon is the largest Gothic palace ever built. Constructed in two main phases by two of its residents, the Palais des Papes is a grandiose architectural expression of the wealth and power of the eleven popes who called Avignon their home and base of power.

In the early 14th Century, all of Italy—but Rome, in particular—was plagued by a constant and pervasive sense of unrest. The ancient city was the arena in which various factions vied for power in a conflict bordering on outright civil war. Meanwhile, tensions were mounting between Pope Boniface VIII and King Philip IV of France, resulting in the premature death of the former and the excommunication of the latter. His short-lived successor, Pope Benedict XI, was the first to vacate Rome, electing instead to make his home in the more northerly city of Perugia; it was Benedict’s successor, Clement V, who would first establish the papacy in Avignon in 1305. In doing so, the new pontiff hoped to begin repairing the Church’s relationship with, and authority over, the Kings of France and England. Escaping the strife of war-torn Italy was a secondary, albeit significant, motivation.[1]

Located between France, Italy, and what would come to be known as Germany, Avignon was an ideal base of operations for Clement V’s mission to restore the Church’s benevolent, but unquestioned, authority over the disparate states of Europe. While Rome had once been the nexus of an empire which had stretched from the British Isles to the Middle East, Avignon was at the center of the medieval Christian world which only encompassed Europe. Its proximity to the intersection of the Rhône and Durance Rivers also made transit from the city to the rest of Europe relatively convenient: a swift messenger could bring news from Avignon to destinations as remote as London or Rome in less than two weeks. Despite these advantages, however, Avignon lacked the historical religious significance of Rome, and it took two decades before one of the city’s pontiffs saw Provence as more than a temporary home for the Church.[2]

Despite sharing his predecessors’ longing to return to Rome, Pope Benedict XII was forced to acknowledge that the continued upheaval in Italy made such a dream untenable. It was then, in 1335, that the austere and sensible Benedict resolved to build a palace to house himself and his court and, in so doing, establish Avignon as his permanent seat of power. He chose to build his new home on the site of the city’s former bishop’s palace, the Bishop of Avignon being compensated with the residence of a recently deceased cardinal.[3]

The architect Benedict XII chose for his palace was Pierre Poisson – a man who, like the Pope himself, was originally from Mirepoix in what is now southwestern France. Poisson oversaw the construction of a roughly rectangular building based on the layout of the bishop’s residence which once occupied the site; in keeping with Benedict XII’s personality, it was an austere structure devoid of sculptural ornamentation and more reminiscent of a protected convent or a fortress than a palace.[4,5]

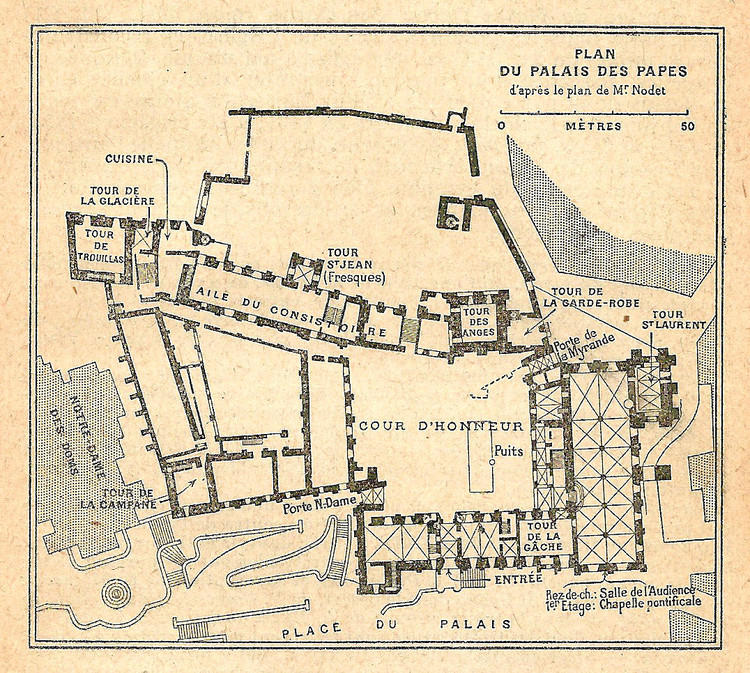

Entry to this first incarnation of the Palais, now deemed the “Old Palace,” was through a fortified entry gatehouse projecting from the southern wing of the building (later demolished during the next major phase of construction). The irregular quadrilateral of the central courtyard was surrounded by galleries two stories tall and dwarfed by the various towers constructed around the building’s periphery.[6] The northern wing contained the palace’s first chapel: 40 meters (131.2 feet) long and only 8 meters (26.2 feet) wide, this chapel was considered disproportionate, too small, and too distant from the Pope’s apartments. These undesirable qualities, combined with the room’s tendency to become unbearably cold in winter, ultimately resulted in the relocation of pontifical ceremonies to a new chapel on the opposite end of the Palais.[7]

The surrounding wings—the Consistoire to the east, the Aile des Familiers to the west, and the Conclave to the south—contained the residences and offices of members of the papal court. The Tour de la Campane, the tallest tower in the “Old Palace” (and still the highest point in the building overall), stood at the northwest corner of the cloister, its crenellated crown dominating the Palais. Jutting from the southeast corner of the palace stood the Tour du Pape (“Pope’s Tower”) or Tour des Anges (“Tower of the Angels”), the wing and tower which contained the apartments of the pontiff himself.[8]

The second major phase of construction, resulting in the “New Palace,” took place under Benedict XII’s immediate successor, Clement VI. Clement VI ordered the completion of the Trouillas and Kitchen Towers at the northeast corner of the Old Palace, as well as the addition of the Wardrobe Tower to the papal apartments. His vision for the Palais des Papes, however, was far grander than that of Benedict XII’s. To execute this greater scope of work, Clement VI commissioned the design services of Jean de Louvres of Île-de-France (the region surrounding Paris). De Louvre immediately set about his work, gathering 600 men and clearing out the neighborhood surrounding the palace to make way for his sizable additions.[9]

Unlike the somber, unadorned “Old Palace,” the New Palace did not shy away from embellishment or grandeur. De Louvres’ first project was the Grand Audience Hall, a 52 meter (170.6 foot) long chamber on the ground floor of the new Grande Chapelle (“Great Chapel”). The hall is crowned with pointed Gothic vaults and adorned with a fresco by the Italian painter Matteo Giovanetti, who painted a composition of 20 figures from the Old Testament for the sizable sum of 600 Florins. Above the Audience Hall was the Great Chapel itself, which, at 52 meters (170.6 feet) by 15 meters (49.2 feet), was over twice the size of the original built under Benedict XII. With the addition of the Great Dignitaries’ Wing—which housed the offices of the notaries and financial officials—to the west, the two wings of the New Palace and the papal quarters of the Old Palace defined a second, larger courtyard.[10,11]

By the time of Clement VI’s death in 1352, the Palais des Papes was essentially complete. Only 25 years later, the papacy finally returned to Rome; after the Great Schism of the late 14th and early 15th Centuries, the palace was subsequently occupied by Legates and Vice-Legates until the French Revolution at the end of the 18th Century. For the next century, the once-prestigious Palais was put to use as a barracks, a role it would play until 1906, when it was opened to the public. Since then, the once-mighty home of the Avignon papacy has undergone significant restoration and repair to preserve its centuries-old architecture for the appreciation of the thousands of visitors who flock to it each year.[12,13] Although the Popes who built the Palais and gave it purpose vacated the massive structure centuries ago, its imposing towers and grandiose Gothic halls stand as a silent reminder of a period in European and Christian history which would otherwise be all too easy to forget.

References

[1] Gagnière, Sylvain. Palais des Papes d'Avignon. Paris: Caisse National des Monuments Historiques, 1965. p7-8.

[2] Renouard, Yves. The Avignon Papacy: 1305-1403. London: Faber & Faber, 1970. p20-36.

[3] Renouard, p40-41.

[4] Gagnière, p16-17.

[5] "The biggest Gothic palace in the world." Palais des Papes - Avignon. Accessed February 26, 2017. [access].

[6] Gagnière, p19-21.

[7] Colombe, Gabriel. Le Palais des Papes d'Avignon. Paris: Société Française d'Archéologie, 1939.

[8] Colombe, p10-55.

[9] “The biggest Gothic palace in the world.”

[10] Gagnière, p67-99.

[11] “The biggest Gothic palace in the world.”

[12] "The Popes' Palace of Avignon." Avignon et Provence. Accessed February 26, 2017. [access].

[13] “The biggest Gothic palace in the world.”